Malmesbury Abbey Ground Penetrating Radar Survey

Download a PDF copy of the full report (15Mb)

Summary

Ground penetrating radar survey was undertaken by Archaeological Surveys Ltd over several areas at Malmesbury Abbey, Abbey House Gardens and The Old Bell Hotel in Malmesbury Wiltshire. The survey was undertaken on behalf of Malmesbury History Society as part of a programme of research into the site.

The survey located a number of anomalies that could be clearly attributed to remains relating to the abbey. These include parts of the cloister, the crossing, north and south transepts and presbytery. Several other anomalies suggest structural features that may also be related to the abbey complex and include remains to the west of the cloister including to the rear of The Old Bell Hotel, possible structural remains to the north east of the cloister and to the north of the footprint of the demolished eastern part of the abbey. Structural remains relating to demolished parts of St Paul's church were also located to the south of the abbey.

Several anomalies to the north of the abbey, within the footprint of the cloister and to the north of the north transept, may represent structural remains pre-dating the Norman abbey. Although the features cannot be confidently interpreted, they have a different orientation to the abbey and may, therefore, pre-date it.

To the south and west of the abbey evidence for widespread and dense burials was located within the churchyard. There was no evidence of structural remains within these areas but given the density of burials and the associated ground disturbance, evidence of any early features may have been destroyed.

Archaeological background

The earliest recorded settlement at Malmesbury dates to the Iron Age with successive hillfort ramparts and ditches showing evidence of possible timber and later limestone revetment 200m east of the site (Longman et al, 2006). During the 10th or 11th centuries an earth and stone bank was constructed along the line of the hillfort ramparts and subsequent medieval town walls also utilising them (Collard & Harvard, 2011). Residual pottery finds at the site of the Althestan Cinema, just to the south of the abbey, supports the evidence that there was settlement in this area during the Iron Age and Roman periods (Hart & Holbrook, 2011).

Most of the history of Malmesbury Abbey has come to us from the writings of William of Malmesbury (c1090-1143), who was librarian for the abbey during the 12th century. The earliest record relating to any religious establishment was in 637 when Irish monk Maeldulph (or Maeldub) founded a hermitage at Malmesbury. A monastery was established some time between 675 and 705 under abbot Aldhelm and was later under the Benedictine order some time between 965 and 974. Aldhelm built three churches, one in honour of Our Saviour, St Peter and St Paul which was considered the main church of the monastery, one in honour of St Mary and against this, one in honour of St Michael. Two further churches are also recorded, one dedicated to St Andrew and another to St Lawrence (Pugh & Crittall, 1956). It is possible that they were laid out in a linear formation, as at St Augustine's Abbey in Canterbury and Glastonbury Abbey (Robinson & Lea, 2002). However, no evidence for the location or remains of any of these Anglo-Saxon buildings has ever been established through archaeological investigation.

Aldhelm died in 709 and his remains were buried in the church of St Michael and in 837 King Ethelwolf had his bones to be replaced in a silver shrine. In the late 9th century the monastery burnt down, to be rebuilt by King Athelstan in the early 10th century who was buried under the altar of St Mary in the tower. The shrine of Aldhelm was then moved in the mid 10th century by Dunstan to the church of St Mary's and the relics taken from the shrine and placed in a grave on the north side of the alter. The monastery was destroyed by fire a second time in 1042. It is not clear when it was rebuilt, but it must have been done fairly rapidly.

In the 12th century these earlier buildings were replaced by a nave of nine bays, transepts with an eastern chapel on either side, a presbytery of four bays with a round apse, the shrine to St Aldhelm and three chapels on the eastern end. These were believed to be commissioned by Bishop Roger of Salisbury between 1118 and 1139, although it is possible that it may have been commissioned later by French Cluniac abbot, Peter Maurant, possibly completed around 1170-1180. However, the majority of English abbeys and cathedrals were undergoing rebuilding in the first quarter of the 12th century, and Malmesbury would be the exception if it were the late 12th century (Robinson & Lea, 2002). Bishop Roger also constructed a castle in the abbey graveyard during the war between Stephen and Matilda, with it changing hands several times during the Anarchy period (1135-1153). It is not clear if this was sited to the west of the abbey under the site of the present Bell Hotel or to the east under the monastic graveyard as no clear evidence of its siting has been located.

In 1260 William of Colerne became abbot and commenced a period of construction and remodelling of the abbey and ancillary buildings. This included an eastward extension of the presbytery and the Lady Chapel was added with a charnel house and a chapel made for the disturbed bones. In the 14th century a timber and lead spire was added to the crossing and subsequently collapsed around the time of the dissolution. Around 1400 a square tower was built over the two western bays of the nave. A new building was erected over the south side of the nave in the 15th century and the cloisters were rebuilt and vaulted. The abbey remained under the Benedictine order until its dissolution on 15th December 1539, when it was sold to clothier William Stumpe. He built the present Abbey House over some of the monastic buildings in the east of the site and gave the nave of the abbey church to be used as the parish church for Malmesbury. John Leyland, visiting in 1542, wrote that the spire had fallen within living memory and that a small chapel joined the south side of the southern transept. Whether this was the church of St Michael, the church of Our Saviour or the church of St Laurence has been debated (Robinson & Lea, 2002).

The site and surrounding environs have been subject to a small number of archaeological investigations. During the early 20th century Harold Brakspear was commissioned to restore much of the present abbey buildings. During these restorations he conducted a number of excavations within the abbey precinct with grant funding from the Society of Antiquaries (Brakspear, 1914). He excavated in the area of the south transept and quire and found that apart from a small patch of tile paving all the foundations had been robbed out. He was informed that this area had been in private hands and that it previously contained large heaps of debris which had been removed during ground levelling.

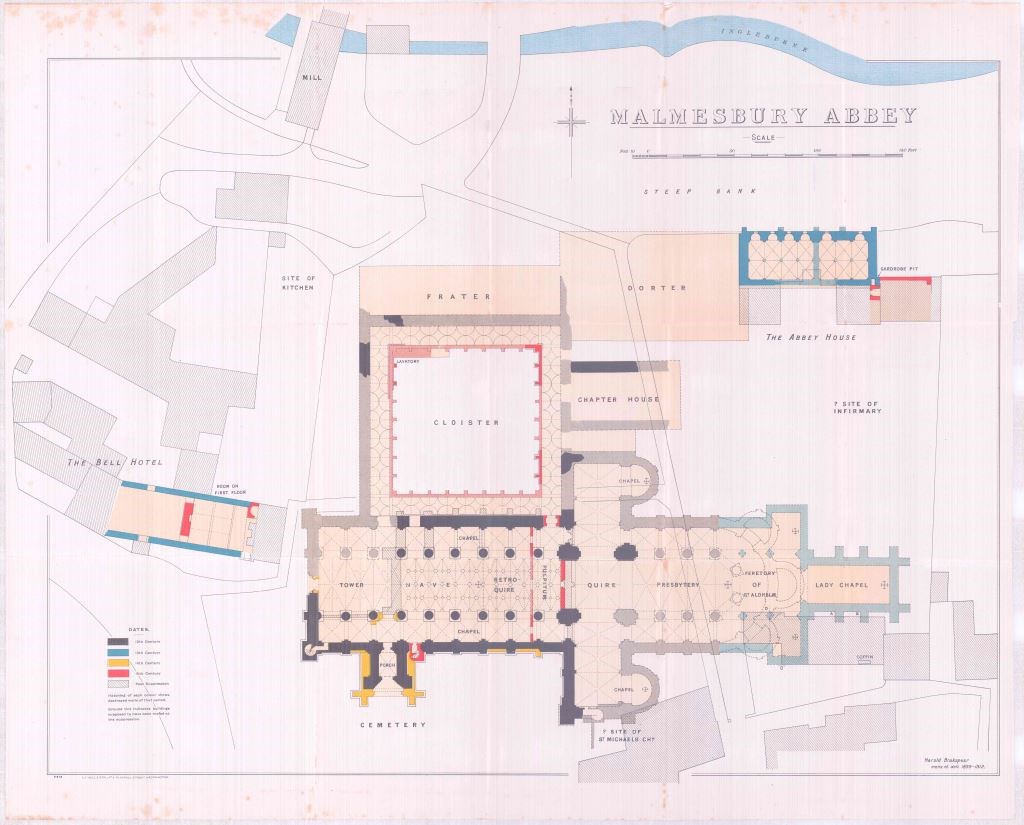

A later grant in 1910 allowed Brakspear to trace the cloisters and surrounding buildings. Although much of the cloister foundations had been robbed, he found fragments of the inner cloister walls in the east and also the outer cloister walls in the north west along with floor tiles. He found evidence for the foundations of a lavatory where the monks would wash in the north western corner of the cloister, as at Gloucester Cathedral. He also established that the 15th century vaulting in the cloister was as elaborate as that at Gloucester. The northern foundation wall of the chapter house was also located; however, the southern wall was built on shallow bed-rock and no foundation was identified. He records a 12ft wide foundation with a rounded outer face lying some 80 feet to the east of the crossing which he ascribes to the ambulatory wall to the rear of the presbytery leading to the three chapels and which dated from the 12th century. This would place it on the western edge of the Abbey House Gardens. He produced a plan of the Norman and later abbey, Plate 1, based on the upstanding building as well as from his excavations and conjecture of the remainder of the church to the east. He does not appear to have located any structural remains pre-dating the Norman period.

A geophysical survey was carried out over the area of the cloisters, west end of the abbey as well as in Abbey House Gardens (Bartlett, 1997). Earth resistance survey (resistivity) supported the evidence from Brakspear's plan for the north wall of the west end; however, later evaluation in this area indicated that the north wall had been robbed out (Kenyon, 2003). The resistivity survey also indicated high resistance responses to the east of the nave, the north wall of the chancel (presbytery) beneath the central crossing arches, the north and south chancel arcades and the eastern wall of the southern transept. There was also a correlation between Brakspear's planned reconstruction and the walling within the cloister. No anomalies could be clearly seen to correspond to the north transept and chapter house although a number of irregular high resistance responses could relate to fragmentary masonry remains. Within Abbey House Gardens a number of high resistance anomalies correspond with the 12th century apsidal east end of the church and the three radiating chapels, with a weaker response to the east possibly associated with the 13th century Lady Chapel. It is not clear if anomalies further to the east relate to former structures or to previous more recent paths and garden features.

In 2002 an archaeological excavation within the site of the former Athelstan Cinema, located immediately south of the southern transept, found evidence for two short sections of limestone walling and evidence for medieval floor make-up. This may relate to a probable chapel, possibly that seen by Leyland in 1542 in this area. There was no evidence to support an Anglo-Saxon origin for the probable chapel, although this could have remained beyond the exposures in the excavation (Hart & Holbrook, 2011). A number of burials were also located to the south, with evidence for disturbance and truncation of earlier graves by later burials. They were mainly male burials, which could relate to the monastery but there were some female and child burials indicating that the laity were also buried in this area. Several were laid out in evenly spaced rows and date no earlier than the mid 12th century and no later than the end of the 13th century.

In early 2003, during the replacement and installation of new external floodlighting at the abbey, a 19th century brick-lined grave and a modern or post-medieval wall were located within the cable trench immediately to the west of the path that leads from the south gate to the abbey porch . Within the trench to the north of the northern crossing arch, east of the abbey church were quantities of building rubble most likely to have been derived from the demolition of the former buildings. The majority of the finds within the trenches were of 18th - 20th century origin (Foundations Archaeology, 2003).

Further evaluation was also carried out immediately west of the abbey (Kenyon, 2003), which revealed seven phases of development, construction and demolition between the 12th and 20th centuries. Prior to the 12th century construction of the abbey, the ground was levelled through a combination of ground make-up and terracing upon which the west face of the abbey was constructed in a single phase. Although a previous geophysical survey (Bartlett, 1997) within this area identified possible flooring external to the original west doorway, no flooring evidence was seen during the evaluation. Post-dissolution, the flooring, together with tiles and walling, were removed from above ground and footings and this is likely to have begun just after the west tower collapsed in the later 16th century, but is likely to have continued into the post-medieval period. During the 18th century a number of stables, hovels and pig styes were removed from the western end of the church and the remains of their flooring were evident. A 19th century plinth for the display of a Russian cannon from the Crimean War of 1854-5 was also uncovered. During the early 20th century renovations of the abbey by Brakspear, a number of drains were laid and two large charnel pits have been interpreted as being for the re-interring of human remains disturbed during the renovations. A vestry/office building had been constructed in the north eastern corner of the site and a number of services, many of which served the vestry building, were also located.

All that remains of the abbey is the nave of the church, the north and south aisles, the south porch, some of the western wall of the southern transept and part of the northern crossing. Brakspear's plan places the crossing in the centre of the building, with part of the presbytery in the garden of remembrance to the east of the abbey and the remainder in the Abbey House Gardens. Much of this lies under hedges and areas of planting and so was not accessible for survey.

The church today is known as St Mary and St Aldhelm's Abbey Church and the building, along with a wider area to the north and east including Abbey House and Gardens, is part of a scheduled monument of the Benedictine monastery known as Malmesbury Abbey (Historic England List Entry no. 1010136). This includes six bays of the nave that remained after the west tower fell down in the 16th century and also the buried remains of the medieval cloisters to the north, together with the chapter house to the east of the cloister and the dorter to the north of the chapter house. The site of St Paul's church, 50m to the south of the abbey, is a separate scheduled monument (St Paul's Church tower and site of church, Historic England List Entry no. 1004682). Although the earlier church of St Peter and St Paul may have stood on the site, the remains of the present church are believed to date to around 1300, with the spire added around 1400. The orientation of the tower is east north east to west south west, parallel with Oxford Street to the south, rather than the abbey church to the north which is east west. By the later 9th century, Malmesbury was one of the four burhs of Wiltshire and it is likely that the street plan was laid out around this time (Baggs et al, 1991).

From the writings of William of Malmesbury it appears that the monastery was originally constructed in the 7th century, but was burnt down and rebuilt at least twice in the late 9th and mid 10th centuries, prior to construction of the 12th century abbey church and buildings. These were later remodelled in the 13th, 14th and 15th centuries, with the central tower and spire collapse likely during the early 16th century and the remaining buildings in a generally very ruinous state from at least the late 18th century. There is no archaeological record of the location of the Anglo-Saxon monastery buildings; when Brakspear (1914) excavated in the early 20th century, he was able to imply the layout of the Norman abbey church, but he does not appear to have located anything pre-dating this. Archaeological evaluation to the south of the present southern transept may have located a chapel, possibly that of St Michael, but this too relates to the Norman abbey, with a number of 12th/13th century burials nearby, and none dating to before this period (Hart & Holbrook, 2011). No features earlier than the 12th century were recorded to the west of the abbey church (Kenyon, 2003). However, the lack of identification of any Anglo-Saxon buildings could be due to several factors, such as no archaeological evaluation within the areas of the earlier buildings or that they lie directly underneath the later buildings. The GPR survey was undertaken within the present abbey church and in all accessible areas outside including the graveyard, cloisters and Abbey House Gardens in order to cover as wide an area as possible.

References

Baggs, A.P., Freeman, J., and Stevenson, J. H., 1991. 'Parishes: Malmesbury' in A History of the County of Wiltshire. Vol 14, Malmesbury Hundred, pp 127-168. British History Online available from http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/wilts/vol14/pp127-168. [accessed 26/02/2018].

Bartholomew, R., 2010. A History of Malmesbury Abbey. The Friends of Malmesbury Abbey, Malmesbury.

Bartlett, A., 1997. Malmesbury Abbey, Report on Archaeogeophysical Survey 1996, Bartlett-Clark Consultancy. Unpublished typescript document.

Brakspear, H., 1914. 'Malmesbury Abbey'. Wiltshire Archaeological & Natural History Magazine, vol. 38, pp 458-497.

Collard, M., & Harvard, T., 2011. 'The prehistoric and medieval defences of Malmesbury: archaeological investigations at Holloway, 2005-2006'. Wiltshire Archaeological & Natural History Magazine, vol. 104, pp 79-94.

Foundations Archaeology, 2003. Malmesbury Abbey: Archaeological Watching Brief. Unpublished typescript document.

Hart. J., & Holbrook, N., 2011. 'A medieval monastic cemetery within the precinct of Malmesbury Abbey: excavations at the Old Cinema Site, Market Cross'. Wiltshire Archaeological & Natural History Magazine, vol. 104, pp 166-192.

Kenyon, 2003. Malmesbury Abbey West End, Malmesbury, Wiltshire. Archaeological Evaluation. Report ref. 03075. Unpublished typescript document.

Longman. T., 2006. 'Iron Age and later defences at Malmesbury: Excavations 1998-2000'. Wiltshire Archaeological & Natural History Magazine, vol. 99, pp 104-164.

Pugh, R., B., and Crittall, E., 1956. 'House of Benedictine monks: Abbey of Malmesbury' in A History of the County of Wiltshire. Vol 3, pp 210-231. British History Online available from http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/wilts/vol3/pp210-231 [accessed 26/02/2018].

Robinson, D., M., & Lea, R., 2002. Malmesbury Abbey, History, Archaeology and Architecture to Illustrate the Significance of the South Aisle Screen. Historical Analysis & Research Team, Reports and Papers 61. English Heritage.